(Cross-posted at FacilitatedCommunication.org).

Part I: The Psychologist

When it comes to facilitated communication, Psychology Today has a mixed record. While a number of its contributors (Amy Lutz, Stephen Camarata, Bill Ahearn, and Scott Lilienfeld) have spoken out against it, others (Chantal Sicile-Kira, Robert Chapman, and Susan Senator) have, to one degree or another, expressed support. Recently joining the second cohort (which consists of a neurodiversity philosopher, an autism consultant, and an autism parent) is a psychologist: Debra Brause, PsychD.

Brause’s post, entitled Nina: A Nonspeaker Who Found Her Voice, showcases a nonspeaking autistic individual who purportedly describes her feelings of being locked inside and unheard by others until she started “using a method called spelling to communicate (S2C), which enables her to share her story.” S2C has also enabled Meehan’s communication partners to conclude that “she is a deep thinker and cares about ‘every single thing’” and also that she’s bilingual:

Not only did Meehan know English, but likely due to exposure to her grandmother’s native language, one day, Meehan spelled in Spanish, “I’m bilingual. I know how to speak Spanish, too.”

Brause is aware of the controversy surrounding facilitated communication (FC) and variants like S2C and RPM (Rapid Prompting Method). But she’s nonetheless confident of her claims. Nor are all of them unreasonable, as we see in her first two bullet points:

Access to communication is a fundamental human right.

Misconceptions about nonspeaking autism can be harmful.

Indeed; I think we can all agree on those.

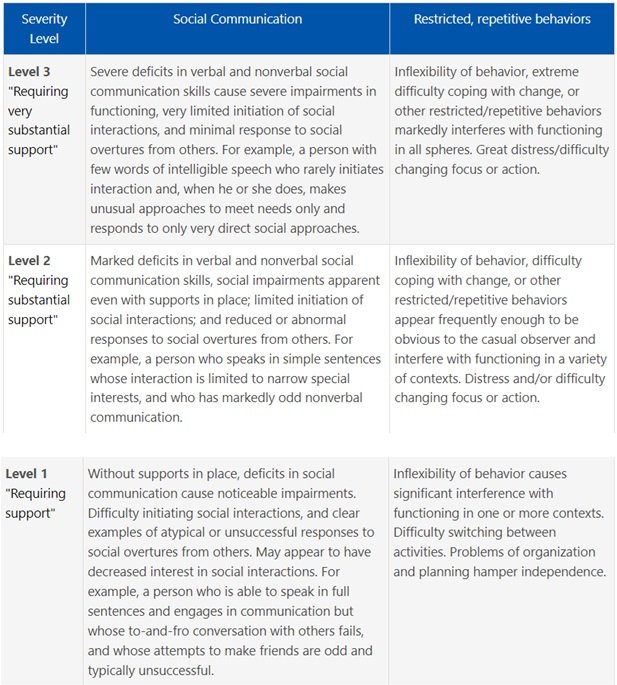

But then come the next two bullets, which are, in fact, two harmful misconceptions about nonspeaking autism:

Spelling to communicate (S2C) can be a powerful tool for nonspeaking autistic people.

Neurotypicals should presume competence and become helpful communication/regulation partners to nonspeakers.

In fact, as a careful read through this website’s research pages (see here and here) will show, all the available evidence indicates that in S2C, as with all other forms of facilitated communication (FC), the facilitator, not the person with disabilities, is controlling the messages. S2C, thus, quite far from being a powerful communication tool for nonspeakers, is likely a major suppressor of their communication rights, as well as being a major detractor from evidence-based therapies that boost—however slightly—the ability of these vulnerable individuals to communicate authentic messages independently.

Additional harms can come from the specific messages and associated desires that are attributed to these individuals. Consider this:

Recently, Meehan met another local speller named Wynston. They started hanging out, and Wynston asked her to be his Valentine. They are forming a deep and loving emotional connection. Through spelling, they can fully express their feelings for each other, and they hope that other spellers out there know that they can build meaningful relationships, too.

What if Meehan actually has no interest in having a relationship with Wynston, and/or vice versa? What happens if Meehan and Wynston are forced to spend time together, even live together, against the will of one or both of them?

And what if Meehan actually has no interest in the causes that are attributed to her through her facilitated output and would rather be doing something entirely different:

She wants to create a school where spellers thrive. She is asking for neurotypicals to see what nonspeakers are capable of and give them the chance to have meaningful opportunities in society. She has created The Nina Foundation to educate the world about autism and raise awareness about autistic people’s ability to comprehend the world around them. According to Meehan, “There is a revolution happening through unlocking the voices of all nonspeakers.”

Nor is presuming competence the right move for neurotypicals who work with nonspeakers on communication—or, for that matter, for anyone who works with anyone on anything. If I were to presume that my special ed students are already competent, say, in understanding what constitutes an autism-friendly learning environment, I would do them (and their future students) a huge disservice. And if certain of my college mathematics professors hadn’t presumed, say, that we students were already competent in abstract math proofs, we all would have become better at constructing and applying these proofs on our own. What good teachers presume isn’t their students’ competence, but their capacity to learn what they don’t yet know.

Brause, however, is confident that we skeptics are wrong. One of her criticisms is that familiar straw man: “there is a common misconception that autistic nonspeakers do not have cognitive ability.” But it’s well known that autistic nonspeakers can excel in nonverbal tasks like puzzles, math, art, and music. What autistic nonspeakers don’t excel in is language. That’s because autistic nonspeakers—unlike nonspeakers with paralysis or deafness—are limited, by their very autism, in their automatic attention to voices and faces and in their ability to figure out the meanings of words.

Another of Brause’s criticisms repeats the “presume competence” fallacy:

When we assume that those without a voice are not verbal, we demean their capability and fail to uncover the intelligence they hold inside.

But the best way to uncover hidden intelligence in those without a voice is to provide evidence-based language instruction; not to assume that they’re already verbal.

Brause also repeats the popular but evidence-free pro-FC claim that apraxia impedes the ability to demonstrate comprehension and that S2C addresses this:

Due to apraxia, a motor movement disorder, many autistic people cannot demonstrate what they understand. Apraxia is a disconnection between the brain and the body, and autistic people often struggle to get their bodies to do what their minds intend. Nonspeakers cannot show their verbal acuity without the motor skills to convey their intelligence.

(For a discussion of why this claim is evidence-free, see this post and its follow-up).

Relatedly, Brause claims that S2C helps these theoretically apraxic individuals bypass their motor challenges:

Spelling to communicate teaches individuals with motor challenges the purposeful motor skills necessary to point to letters as a means of communication. The goal is to achieve synchrony between cognition and motor.

This claim, repeated though it is throughout the promotional material for S2C, is also evidence-free.

Another common pro-FC claim echoed here by Brause is that AAC devices are limiting:

The trouble with many AAC devices is that they are limited to icons and don’t represent natural speech. The devices rely on limited choices that can perpetuate motor loops (getting stuck on one icon or word) that may not reflect what the person really wants to say.

In fact, as we point out most recently here, most electronic AAC devices have ABC or QWERTY keyboard modalities that allow open-ended communication through independent, un-facilitated typing.

Interestingly, the only evidence that Brause cites for the validity of S2C is Jaswal et al.’s highly flawed eye-tracking study, and the only specific item she pulls from this article is the following undigested quote: “Our data suggest that participants actively generated their own text, fixating and pointing to letters they selected themselves.” For critiques of the study’s methodology and conclusions, see here and here.

Rather than citing any evidence that actually supports S2C—there isn’t any—Brause mentions its “rigorous training” and its “prompt hierarchy.” Alas, rigorous training does not a valid practice make. And prompt hierarchies, in the worlds of S2C and other FC variants, simply mean prompts that grow more subtle over time (as cues naturally do). Indeed, this notion is one of the biggest distinctions between FC and evidence-based therapies like ABA. In ABA, prompts are eliminated as soon as possible so that the person learns to perform the targeted skill spontaneously (e.g., communicating an unrehearsed message) without the therapist(s)/assistant(s)/facilitator(s) being present. While such independent, spontaneous performances of previously unmastered skills are routinely achieved in ABA, the same has never been documented in S2C or any other FC variants.

Brause’s other substitute for evidence, in particular for the claim that the S2C facilitator is “never influencing the content of the speller’s message”, is the movie Spellers. (For our critique of this highly problematic S2C documercial, see here).

Elaborating on the question of facilitator influence, Brause is convinced that S2C and RPM are essentially different from traditional FC:

The concern amongst skeptics is that the facilitator is the one conveying their own thoughts. Rapid prompting method (RPM) and S2C, however, differ from FC in that the facilitators do not typically support the child’s hand or arm and instead hold or move a letterboard.

It doesn’t seem to occur to Brause that prompts and letterboard movements (combined with facilitator judgments about which letters have been selected) are just as powerful at guiding messages as supporting a hand or arm. For examples of how this works, see, again, our review of Spellers.

Brause does acknowledge that the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) has a position statement against S2C—though she mentions only the second of ASHA’s two concerns, “lack of scientific validity,” and mysteriously omits its first concern, “prompt dependency.” Brause proceeds to suggest that what’s at issue is simply a lack of evidence and that this lack of evidence is merely the result of insufficient interest and insufficient funding:

This is an emerging field, and having sufficient research means having the necessary interest from the public and funding from large institutions.

Omitted from Brause’s discussion are the following points:

Many of us are eager to conduct rigorous message passing tests on interested S2C practitioners; the lack of interest is on the part of practitioners, who uniformly refuse to participate in rigorous message passing tests.

Rigorous message passing tests are the only way to determine who is authoring the messages and therefore whether S2C is (a) a valid mode of communication or (b) a communication-suppressing, human-rights-violating procedure.

Rigorous message passing tests are inexpensive and do not require funding from “large institutions.”

In assuming that rigorous research has to be expensive, Brause may be thinking of Jaswal’s eye-tracking study, and/or his more recent flashing letters study, both of which use fancy equipment that might, to untrained eyes, lend a veneer of rigor to his work, but which actually bypass straightforward, reliable measures of authorship and instead generate highly indeterminate results.

Brause concludes by citing the criticisms on the pro-FC website United for Communication Choice of ASHA’s position statements against RPM and S2C as “flawed and dangerous,” singling out this quote from speech-language pathologist and “family communication coach” Gabriele Nicolet:

In ASHA’s own language, evidence-based practice includes the inclusion of people’s clinical and lived experiences. To deny someone’s lived experience and call it a hoax is the opposite of what that organization stands for. It’s abhorrent.

The answer that pro-RPM and S2C practitioners refuse to explore, of course, is the question of what is and isn’t indicative of a facilitated person’s lived experience. And until we conduct rigorous message-passing tests to determine who is authoring the RPM and S2C-generated messages, that question will remain unanswered.

So will the question of whether Meehan actually wants to be in a relationship with Wynston.

Part II: The Journalist

When I first heard that Blocked and Reported, which bills itself as a podcast about Internet nonsense, was running a segment entitled Facilitating Communication (with Helen Lewis), I was hopeful that we’d finally have a wide-reaching, if somewhat offbeat, broadcasting of some powerful FC skepticism.

As it turns out, the show was somewhat of a missed opportunity.

The main problem was that journalist Helen Lewis, a staff writer at the Atlantic, limited herself to traditional FC and to events that occurred many years ago. When going over FC’s early history, Lewis got most of it right—although she referred to Douglas Biklen, who brought FC to the U.S. from Australia, as a “psychologist” and cited one of D.N. Cardinal’s early papers as having positive results for some individuals under controlled conditions (see our critique of that paper here).

Lewis did a pretty good job discussing the ideomotor (Ouija Board) effect and emphasizing the likelihood that FCed messages are entirely controlled by the facilitator—although she claimed, incorrectly, that “Some really did progress to independent communication.” She clarified that that this purportedly successful subset consists of those whose problem “was fundamentally a motor problem,” citing “locked-in syndrome” as her one example. But she added that “You can’t tell just from looking at someone whether they are one of the genuinely locked in people”—neglecting to clarify that “genuinely locked in people,” unlike most of the minimally verbal individuals who are subjected to FC, aren’t born that way and have typically been able to communicate independently prior to whatever injury locked them in.

Lewis went on to discuss such landmarks as the anti-FC exposé Prisoners of Silence, Janyce’s story as recounted in Prisoners of Silence and Janyce’s subsequent anti-FC activism (Lewis is highly appreciative of Janyce!); the pro-FC movie Autism is a World; Dan Engber's New York Times Magazine article about the Anna Stubblefield Case; and, finally, what seems to have been the impetus for this interview: the Anna Stubblefield movie that was released in the UK earlier this year and has yet to air in the U.S.

The closest Lewis comes to acknowledging the newer variants of FC is to discuss David Mitchell’s promotion of Naoki Higashida (The Reason I Jump). She rightfully calls Naoki’s communication a form of FC even though no one touches his arm, noting how suspiciously sophisticated his language is and how much it resembles all the other suspiciously sophisticated FC-generated messages she’s encountered.

But then Lewis suggests that FC is on its way out. She cites the renaming of the Facilitated Communication Institute at Syracuse University (now the Center on Disability and Inclusion), claiming that “it says it doesn’t advocate for things like FC, where there’s ambiguity regarding whether the client or the facilitator is the source of the message.” She apparently didn’t explore the Center’s website thoroughly enough to come across this page, which makes clear that FC is still very much a part of the Center’s activities. Instead, Lewis offers this: “I would say at this point that FC is pretty kind of trashed really.”

Nor does Lewis seem to have any idea of the latest variants of FC that are proliferating all over the country at what appears to be a geometric rate, thanks most recently to that documercial for S2C—which likewise goes unmentioned by Lewis.

Interestingly, Lewis concludes her interview by noting that journalists sometimes get things “catastrophically wrong”, and that, should she ever be caught doing that herself, “it will be a major test of character whether I’ve got the balls to just go ‘Nope, really spooned that one, absolutely sorry to everyone’.”

I’m rooting for Lewis to pass that test.